The city was a place of soft decay, a grey malaise that had seeped into the mortar and the marrow of its people. Elias worked as a junior archivist, a job that smelled of dust and slow-going despair. His days were spent mending the brittle spines of forgotten ledgers, his fingers stained with the grime of other people’s histories. He was a model of quiet quitting, though he’d never heard the term; a body in a chair, a ghost at a desk, his spirit having long since tendered its resignation.

It began with a pressure in his jaw, a dull ache that wasn’t pain so much as a prompt. Instinctively, he found himself pressing his tongue flat against the ridged palate of his mouth, holding it there. A quiet, constant pressure. At first, it was a distraction from the thinning soup and the damp chill of economy that clung to his small flat. But then, the pressure began to answer back.

His world started to change, not in sight, but in scent. The stale air of the archives, once a uniform blanket of old paper, began to separate into distinct notes: the sweet rot of foxed paper, the acidic tang of cheap ink, the faint, mineral ghost of the rag-and-bone men who’d made the parchment. On the street, the perfume of a passing woman was a nauseating shriek, but the scent of rain on hot asphalt, of moss growing in the cracks of a wall—these were balms. He found himself drawn to the city’s forgotten corners, the overgrown towpaths and forgotten churchyards, places where the green and the damp were staging a quiet coup.

His flat, once tidy and anonymous, began to reflect his burgeoning authenticity. He brought things home. A piece of bark colonized by a filigree of emerald moss. A smooth, grey river stone. The bleached shoulder blade of a fox he found near the railway line. He laid them out on his windowsill, a private altar to the textures and smells that now felt more real than his own reflection. It was a kind of goblin-core aesthetic, a curation of the beautiful and the grotesque, a home for a self he was only just beginning to meet.

His landlady, Mrs. Gable, complained about the earthy smell, about the dirt he tracked up the stairs. “It’s not healthy, Mr. Arkwright,” she’d say, her face a mask of pinched concern. “All this… foraging. People will talk. They’ll think you’re delulu.”

He’d just nod, the pressure in his jaw unwavering. The ache was a comfort now, a conversation. It was in his sleep that it grew loudest. He dreamt of a different mouth. A mouth with more teeth, longer and sharper, designed for tearing and cracking, not for the mushy civility of cooked food. He woke with his gums throbbing, a phantom agony that felt like a memory. An echo of teeth he’d never had.

At work, he stopped speaking unless absolutely necessary. The sounds of human speech had become grating, the vowels too round, the consonants too soft. He packed his lunch, but it was just for show. Instead, during his break, he’d go to the small park and chew on bitter roots he’d pulled from the earth, the grit a welcome texture, the raw, living taste a shock of pure vitality. He was losing weight, his face hollowing out, his jawline becoming ferociously sharp. His colleagues gave him a wide berth. They thought he was starving. In truth, he had never felt so sated.

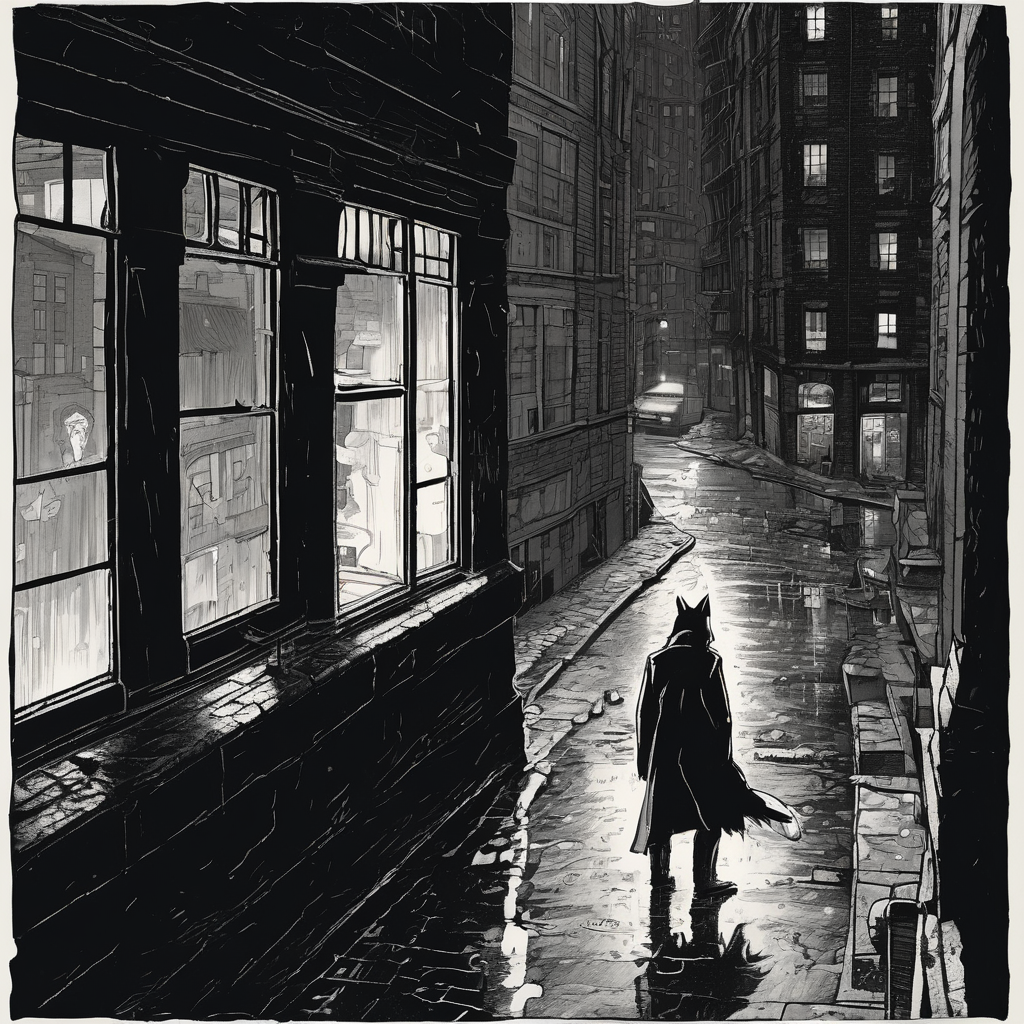

The transformation was not about becoming a monster. It was about ceasing to be an imposter. His human life, his quiet job, his threadbare coat—it was all a poorly-fitting costume. He felt a profound vulnerability in this shedding, a fear that he would be caught between worlds, but the pull towards his true self was too strong to resist.

One night, the ache in his gums became an undeniable, seismic shift. He knelt on the floor of his flat, hands clamped to his face, as a grinding, cracking sound filled the small room. It was not a sound of breaking, but of arrival. When the pressure subsided, he ran his tongue over his teeth. They were different. The canines were longer, sharper, and behind his molars, new, hard ridges had emerged, serrated and strong.

He looked around the room—at the ledgers he’d brought home out of habit, at the single, dusty lightbulb, at the notice of a rent increase on the table. It was a language he no longer understood. He went to his collection on the windowsill and picked up the fox’s shoulder blade, biting down. The bone gave a satisfying crack, and the taste of the marrow, faint and chalky, was a revelation.

Elias opened his window. The night air was thick with the scent of wet earth and distant refuse, a complex perfume of life and decay. He climbed out, his bare feet finding purchase on the slick brickwork with an uncanny ease. He didn’t look back. He was following a scent only he could smell, an invitation from the dark, damp, authentic world that had been waiting for him all along. He was heading for the river, for the deep culverts, for the places where the city’s heart of concrete gave way to mud and bone and teeth.

Leave a Reply